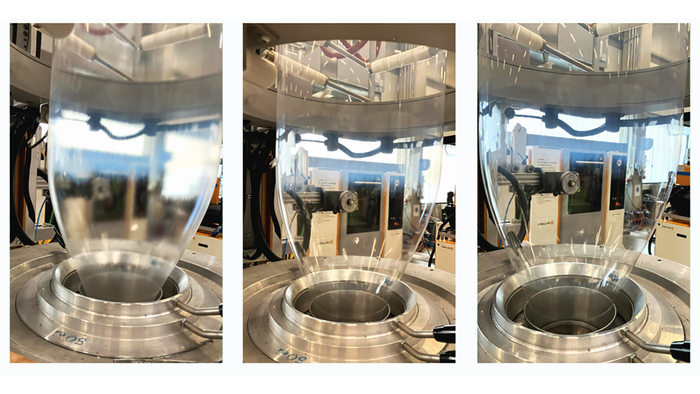

Making contact lens moulds – how do they do it? - soft plastic mould

Author:gly Date: 2024-09-30

The dyes used on in-mold labels for the American market and its requirements can be washed off as the intent is to recycle the labels and the packaging.

The centre, established in 2022, aims to promote the transition to sustainable plastics through capacity building, developing technology for new products and facilitating linkages across the value chain.

Meanwhile, the centre’s industry and governmental partners span the value chain, including bioplastics manufacturer Plantic Technologies, international manufacturing giant Kimberly-Clark and philanthropic organisation the Minderoo Foundation. The centre also collaborates with the Council of the City of Gold Coast and the Queensland government.

In cooperation with partners Alpla Group, Brink Recycling, IPB Printing, injection molding machine manufacturer Engel is presenting a step forward for the packaging industry at K 2022 by processing recycled material, rPET, at its stand. Featured will be an Engel e-speed injection molding machine with a newly developed and extremely powerful injection unit.

With the use of integrated in-mold labeling (IML), the containers are ready-for-filling as soon as they leave the production cell. The special feature in this application is the material. The thin-walled containers are produced directly from rPET in a single step.

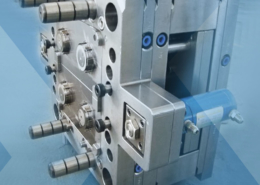

Engel is presenting a mold at the K show which can process different labels at the same time. This sees the partners respond to the globally different trends in in-mold labeling which are in line with the EPBP and/or Recyclass recommendations in the EU, and with the specifications from the Association of Plastic Recyclers (APR) for the USA.

Engel and partners’ development yields thin-walled food containers made in a single injection-molding step using up to 100% recycled PET.

To date, PET is the only packaging material which can be processed as a recycled material on an industrial scale to create food packaging. This innovation sees partner companies pave the way for removing the need to downcycle packaging products other than bottles, and opens an opportunity for recycling or upcycling. This would substantially extend the range of uses for PET and rPET. In addition to the bottle-to-bottle cycle, this also means that the establishment of bottle-to-cup or even a cup-to-bottle recycling is conceivable.

Engel will present this technology and other developments at K 2022 in Düsseldorf, Germany, from Oct. 19 to 26, in booth C58 in Hall 15.

Centre researchers are also developing technologies to produce materials with the right characteristics. “Specifically, we are conducting research to make bioplastics cheaper, tougher, more readily processable and with even better barrier properties,” Pratt says.

In 2022, the global bioplastics and biopolymers market was $11.5 billion (£9.42 billion) and is projected to more than double in the next five years, driven in large part by consumer demand.

To achieve that, the centre is purposefully interdisciplinary. “We certainly have a number of lead researchers who are looking at making bioplastic products, but we also have social scientists looking at supply chains and the expectations of the market, biological scientists looking at how biodegradable plastics behave in the environment, and we also have systems engineers asking what happens if you take the biomass needed to make the products and divert it from what it’s currently used for,” says Pratt. “What does that mean for other systems we might impact?”

Global plastic waste more than doubled between 2000 and 2019, rising to more than 350 million tonnes, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. It is estimated that, without intervention, this waste will triple by 2060 to 1 billion tonnes. About 40 per cent of plastic waste is from packaging.

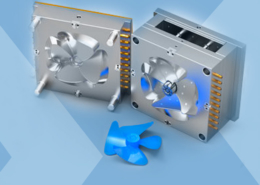

An Engel e-speed 280/50 injection molding machine is the heart of the production cell. Engel specifically developed this hybrid machine with its electrical clamping unit and hydraulic injection unit for the high-performance requirements of thin-wall injection molding.

Under the European Plastics Pact, the intent is for all plastic packaging to contain 30% recycled material and to be 100% recycling capable by 2025. Typical materials used for packaging foods in thin-walled containers are polyolefins (polyethylene, polypropylene) or polystyrene.

Featuring a wall thickness of 0.32mm/0.013 inch, the transparent, round 125-mL containers are representative of a whole category of plastic packaging, especially in the food industry.

Until now, it has only been possible to process PET in thick-walled parts such as bottle preforms in injection molding. In that standard process, the final packaging format was created in a second step of the process — by blow molding, for example.

Pratt has big ambitions for the centre, both in terms of its research output and its commercial applications. “One ambition is a larger research group, where we look at tackling emerging challenges that the rapidly growing industry will inevitably face. Another is the commercialisation of some of the research that is already underway. On top of that, we’re also pretty keen on physically having a production facility through which we’ll be able to contribute to the global supply of PHA bioplastics,” he says.

An Engel spokesperson tells PlasticsToday that, among others, “the [rPET] cups can be used for food products such as dairy products, gourmet salads, or sandwich spreads.”

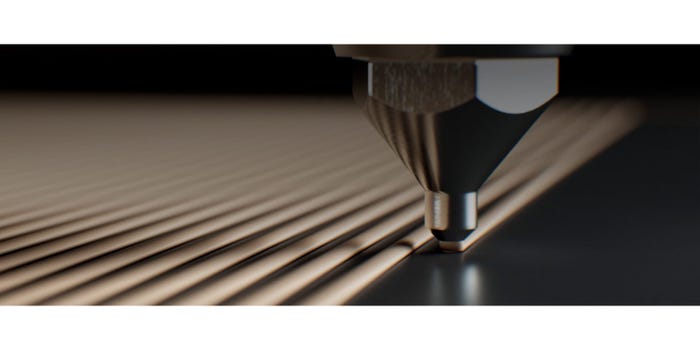

To process rPET, Engel combines the new injection unit with a plasticizing unit from in-house development and production specifically designed for processing recycled material. During plasticizing and injection, the viscosity of the PET is configured for thin-wall injection molding. The new Engel e-speed supports the processing of arbitrary recycled materials up to 100% rPET.

Research is inextricably linked to training and industry-readiness. Lawless, who is one of the centre’s 19 PhD students, is currently on a four-month placement with bioplastic manufacturer Plantic in Melbourne. “I aim to work for industry after completion of my PhD,” says Lawless. The placement is “providing me with valuable industry experience and connections”.

Bioplastics can help address the “wicked problem” of plastic pollution, but companies and research institutions need to take a holistic approach, says Steven Pratt, director of the University of Queensland’s ARC Training Centre for Bioplastics and Biocomposites.

“We are trying to make bioplastics cheaper and make sense commercially,” says associate professor Pratt, who has been working on bioplastics for more than two decades. Bioplastics is an umbrella term that includes plastics that are biodegradable, derived from biological sources rather than fossil fuels, or both.

A different technology is used in Europe: an in-mold label that floats during the recycling process makes it easy to separate the dyes and the label from the PET.

Also, recycling schemes for these materials lack the approval of the European food authority, European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). rPET offers a solution for avoiding penalties and special taxes. Although the price for PET is currently high, this concept makes the material a cost-effective alternative. EFSA has approved numerous recycling processes for PET, thus ensuring that rPET is available in Europe.

One example is polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA), which is already commercially available and approved for food contact. It is used for trays, cutlery and straws, and also services the eco-conscious market as material for moulded toys and eyewear frames. PHA is bio-derived and biodegradable in soil and marine, but the cheapest PHAs have a low melt strength making them difficult to blow into a plastic film, says Pratt. Sam Lawless, a doctoral candidate at the centre, has modified PHBV to improve its properties. “He has already used [his innovation] to blow films as thin as 40 micrometres [which is about half the width of a human hair] and is the desired thickness for plastic films in many film applications,” Pratt says.

Nurturing industry-ready researchers is a vital part of the centre’s purpose. “Yes, these PhD students and early-career researchers are currently working on addressing some of today’s challenges to widespread adoption of bioplastics and composites,” says Pratt. “But, most significantly, they are being equipped to invest, design and implement the new bio-derived and biodegradable products of the 2030s and beyond.”

For the first time, thin-walled containers made of PET, specifically recycled PET (rPET), can be produced in a single injection-molding process step.

The new model 280 e-speed high-performance injection unit for K 2022 (shown above) achieves injection speeds up 1,400 mm/55 inches per second at a maximum injection pressure of up to 2,600 bar when processing small shot weights with an extreme wall-thickness-to-flow-path ratio.

Numerous projects at the centre are investigating the various aspects of bioplastics production. “We have a research programme that seriously tackles the current barriers to widespread adoption,” he says. It includes the relationships between feedstocks, applications, markets and end-of-life impacts.

Rick Lingle is Senior Technical Editor, Packaging Digest and PlasticsToday. He’s been a packaging media journalist since 1985 specializing in food, beverage and plastic markets. He has a chemistry degree from Clarke College and has worked in food industry R&D for Standard Brands/Nabisco and the R.T. French Co. Reach him at [email protected] or 630-481-1426.

The modified rPET being processed at the K show is sourced from PET beverage bottles recycled in the plants of packaging and recycling specialists ALPLA Group, which is headquartered in Hard, Austria. Other partner companies involved in the show exhibit are Brink (Harskamp, Netherlands) for the mold and IML automation and IPB Printing (Reusel, Netherlands) for the labels.

Another project is looking to use bioplastics in areas where they must be biodegradable and cannot be retrieved, such as in agriculture. “One advantage offered by biodegradable polymers is the opportunity to control the release of bioactives without leaving unwanted, nondegradable residues,” says Pratt. Ian Levett, a research fellow at the centre, and PhD student Sumedha Amaraweera, built in-house coating equipment to spray-coat fertiliser granules with biopolymers to investigate the slow release of these granules as their coating degrades.

“At the Centre for Bioplastics and Biocomposites, we try to look across the value chain,” Pratt says. “We made a point of looking beyond just technology development for products.”

GETTING A QUOTE WITH LK-MOULD IS FREE AND SIMPLE.

FIND MORE OF OUR SERVICES:

Plastic Molding

Rapid Prototyping

Pressure Die Casting

Parts Assembly