Prices for PE, PS, PVC, PET Trending Flat; PP to Drop - plastic mold price

Author:gly Date: 2024-09-30

The key is to ensure that companies can manufacture contact lens moulds repeatedly with the highest precision and cost efficiently. “For this reason, production using activeFlowBalance only really works on all-electric machines, such as the IntElect. That’s because we can repeatedly stop the screw in the right place to allow the mould to fill naturally. This intervention reduces the cavity pressure and stress in the material. Once one cavity fills it moves on to another one.” Typically, there are between eight and 16 cavities in each moulding tool.

The situation was replicated around the world, with 3D printed PPE filling the void created when lockdowns threw supply chains into disarray at the same time as global demand far outstripped supply. In Wuhan, where Covid-19 was first identified, 200 3D printers meant up to 2,000 pairs of safety goggles could be produced in the vicinity of the Chinese city’s hospitals on a daily basis. In the UK, the National 3D Printing Society called on anyone with a printer to make and distribute PPE in their local area. Over two months from April 2020, more than 250,000 visors were produced.

Using the most state-of-the-art systems available is also a key consideration. For this reason production machines are typically upgraded every five years with new drive systems, controllers and other key components. “As well as reducing the risk of unscheduled downtime, these upgrades also ensure production rates are maximised – and, sometimes, improved – and costs are controlled,” says Flowers.

When Penn State School of International Affairs academic John Gershenson co-founded Kenyan 3D printing firm Kijenzi in 2017, his aim was to democratise the manufacturing process. Having seen that many communities, particularly in remote parts of the world, are cut off from global supply chains, Gershenson wanted to start an organisation that could, he says, make “what is needed, when it’s needed, where it’s needed”. Medical devices were an area of “clear need” and Kijenzi, which is based in Western Kenyan city Kisumu, started life 3D printing replacement knobs for broken malaria-detecting microscopes. When the Covid-19 pandemic hit, the company’s market was transformed literally overnight.

The production process varies widely for lens mould manufacturers. Some specialise in making the lens moulds, which are then shipped globally in sterile conditions and the lenses are made closer to the local market. Others batch-mould the lens moulds and then store them before they are put through the next phase of production.

Gershenson says this became an issue at the start of the pandemic because much of the demand was being met by hobbyists who used low-grade printers and materials and whose products were not therefore able to comply with stringent medical standards. “The problem with 3D printing is that, yes, you can make anything, but that doesn’t mean you should,” he says. “A person with a 3D printer in their garage can make amazing stuff that they need, but that doesn’t mean they can deliver it to a hospital. What’s needed is a quality programme.”

In the meantime, 3D printing is still being used to fill supply-chain gaps that have arisen due to the pandemic. Earlier this month Scottish 3D printing company Abergower launched a Covid-19 test in partnership with Heriot-Watt University’s Medical Device Manufacturing Centre and Scottish Enterprise’s Scottish Manufacturing Advisory Service. The project can print up to 25,000 swab kits every day, with the aim being to reduce reliance on imported testing equipment. That such a scenario has become normalised is, for Gershenson, the biggest positive outcome the pandemic has had on the 3D printing industry.

Nevertheless, production still has to be carefully planned and controlled, to ensure the highest efficiency levels are maintained.

© 2024 Condé Nast. All rights reserved. WIRED may earn a portion of sales from products that are purchased through our site as part of our Affiliate Partnerships with retailers. The material on this site may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, cached or otherwise used, except with the prior written permission of Condé Nast. Ad Choices

“3D printed products were being sold to hospitals, and devices were being put into patients – often patients didn’t know they were being used,” he says. “In the US, over 150 medical devices cleared for use involve some form of 3D printing. A lot are for bone replacements. Everyone has a different shaped knee and before doctors were having to customise them themselves, shaving them down. With 3D printing you can take a scan of the knee and it can be custom made to that person so it fits perfectly.”

“Every single mould used to make a contact lens is produced to a very high level of precision and cannot be reused,” says Flowers, who confirms that the discarded moulds are recycled – but not for lenses. “Because the final lenses are moulded against a surface that has already been injection-moulded, any imperfection within the mould will find its way into the lens,” he explains.

The biggest markets for contact lenses are currently North America, Asia Pacific and Western Europe, with the sector currently worth nearly US$15bn. Since 2011, there has been a steady increase in demand and the lens manufacturers, many of whom are based in Ireland, expect this trend to continue. “Much of this demand is driven by people who no longer want to wear glasses, as well as improvements in lens technology,” says Nigel Flowers, MD of Sumitomo (SHI) Demag UK. “When you have to wear glasses, it is a bit of a compromise, yet today it is easier to not accept those shortfalls.”

Moulders venturing into this specialist sector may also opt for a self-contained cleanroom moulding and packing system to meet ISO Class 7 or 8 standards. “With these types of systems, moulders have the assurance that they’ll be fully compliant with any GAMP and FDA requirements and we would provide the required DQ, IQ and OQ documentation,” says Flowers.

In some ways the pandemic created the perfect environment for 3D printing to thrive in. Back in 2012, IT research company Gartner put 3D printing at the peak of its Hype Cycle for Emerging Technologies, meaning expectations about what it could achieve were deemed to be grossly overinflated. At that point, Gartner analysts felt it would take more than five years for 3D printing to mature beyond a niche market, with the technology then being seen as something people could use at home to print physical objects such as toys and homewares.

Advances in medical science have enabled contact lenses to be widely accessible and demand is growing. Today, there are estimated to be 125 million people who wear contact lenses globally. Sumitomo (SHI) Demag, a supplier of the machinery that produces the moulds for contact lenses, looks at the production process and trends

All these products were being made by traditional manufacturers to be supplied in traditional ways, with items being printed in large factories before being moved into warehouse storage and transported on to hospitals. The pandemic changed all that. Not only were pieces of PPE being made on-site for use as soon as they were made, but other items were being produced in a far more nimble way too. Shanghai-based 3D printing company WinSun, for example, started printing made-to-order isolation wards - concrete quarantine pods that could be printed in two hours and immediately transported by truck to wherever they were needed. In Spain, a public-private consortium in Barcelona created an emergency-use respirator that was in use in numerous hospitals within days of production starting.

While contact lens moulds are not technically classed as medical devices, any airborne contaminants, such as dust and particles from the raw materials, as well as human contaminants such as bacteria, could affect the lens function.

Rules may have been relaxed to allow 3D printing to meet a specific medical need, but Jacobson says new rules will have to be made if 3D printing is ever to meet its full potential. Legislative processes do not move fast, meaning that will “probably take a decade”, he says. “The technology is ready, it’s the laws that are hampering it,” he adds. “Legal systems are always slow to catch up, but now is the time [to do it], when it’s fresh in everyone’s mind.”

For the production of lens moulds, both all-electric and hydraulic injection moulding machines are used – with the bias heavily weighted (90% to 10%) towards all-electric.

For easier cleaning, which is typically done daily, machines are often raised off the ground on feet. Special anti-static paint is also applied to the external walls of the machine to prevent airborne particles from sticking. Periodic deep cleans are advised.

In a relatively new development, bifocal lenses are now being manufactured on a larger scale to correct both near and far vision. With these lenses, the centre has a different magnification than the outer ring of the lens. In addition, some companies produce Toric lenses that are thicker or shaped at the bottom, which sit on the tears on the eye and they will rotate round. “If you’ve got astigmatism, the lens rotates and always ends up in the right place,” says Flowers. “All of this places greater challenges on the machines but breakthroughs are happening all the time,” he says. “We’ve not quite reached the point where we are 3D printing the lens according to someone’s eye, however this might be possible in the future.”

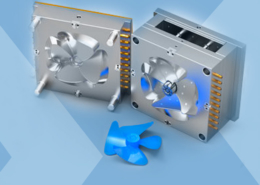

The process starts with the injection moulding of a front and base curve mould. This mould is then filled with a monomer (a molecule that can be bonded to other identical molecules to form a polymer) and is then closed and cured before the lens is then hydrated and packed.

Part of the reason for that is that, despite allowing manufacturing to be localised, on a large scale 3D printing is not as efficient as traditional manufacturing when large numbers of individual products are required. When it closed its PPE initiative last year, the National 3D Printing Society noted that numerous injection moulding companies had been able to set up across the UK in the preceding two months and that the visors they were producing used a “much more efficient and sustainable method of manufacturing”. “Injection moulding not only produces the visors in larger quantities but also increases product consistency and quality,” the organisation said.

“It was clear there was going to be a need for PPE [personal protective equipment] and that, if it came into Kenya, Nairobi would get everything,” Gershenson says. “We had great access to cutting-edge designs – we had access to every product that was getting approved by the World Health Organization – so when the pandemic hit, in less than two weeks, we had completely changed our catalogue and were completely up to speed.”

To accomplish quality and accuracy, Sumitomo (SHI) Demag installs its award-winning activeFlowBalance technology into machines that produce the contact lens moulds. This helps to combat uneven filling of multi-cavity moulds. “When we’ve got to a certain part of the fill and the materials are moving under their own inertia, we stop pushing and let the mould fill naturally. We are not forcing it in at high pressures and forces,” says Flowers.

A variety of moulds are used in the production of contact lenses, representing the different magnification levels (graded in quarter diopters) that are prescribed for each lens. The differences are in the variation in the space thickness between the front and rear of the mould, which dictates the thickness of the lens. There are a finite number of combinations and standard number of magnifications and variations on the curve.

It is anticipated that extra demand for lenses will, in the near future, come from new regions – such as Latin America and Eastern Europe.

Right now only one Sumitomo (SHI) Demag UK customer has opted to automate the entire lens production process. Here, the IntElect injection moulding machine forms just one small part of a huge production line, whereby raw material is put in and the final product comes out the other end packed and ready to ship. “Packing and sealing the lens at the point of manufacture reduces the risk of contamination during moving and storage,” says Flowers.

The quality issue is key, particularly for products being created for use in a hospital environment. In August last year a group of academics from Nanyang Technological University in Singapore wrote a paper that highlighted the downsides involved in 3D printing medical devices. Noting that “safeguarding lives and users’ wellbeing remains a priority”, they stressed that “it is paramount that the 3D printing community works in parallel with medical professionals to avoid creating undue risks to public health”.

Fast forward to 2019 and Gartner was predicting that by 2023 a quarter of medical devices in developed markets would make use of 3D printing, mainly for joint replacement, surgical implants and prosthetics. Matthew Jacobson, a partner in the US law firm Reed Smith’s life sciences health industry group, says that in the pre-pandemic world that was proving to be the case.

Cleanroom Technology keeps decision-makers worldwide updated on contamination control via digital, live, and print platforms. Our articles span the cleanroom lifecycle, from design to maintenance, including monitoring and compliance. Editors deliver breaking news, product launches, and innovations, and also commission exclusives on technical trends from industry experts

Because no two eyes are the same, there are a broad spectrum of styles and parameters to meet when it comes to the production of lenses. Every contact lens that is produced requires a bespoke mould, which is where Sumitomo (SHI) Demag’s injection moulding expertise comes in. Knowing that each lens must meet the highest levels of quality and cleanliness, it is essential that the moulds are repeatedly perfect too.

“Continuous production might be more effective and efficient but the risks are higher,” notes Flowers. “In both instances preventative maintenance and management of downtime has to be well managed. It can be less disruptive to set aside a window every month to switch the machines off and action all the maintenance. This way you can pre-book your engineers. Alternatively, schedule checks for when you are switching moulding tools before production for another type of lens mould commences.”

Meet the contact lens visionaries … then and now Did you know that the first contact lens can be traced back to 1887 and German physiologist Adolf Flick? The lens was made of glass and was called a ‘scleral’ lens because it covered the scleral – the part of the eye that is white. Some years later, in 1912, optician Carl Zeiss developed a glass lens that fitted over the cornea. The first plastic lens (manufactured from plexiglass) is believed to be the work of two scientists, who created the scleral lens in 1938. The first plastic corneal lens arrived in 1948. Among the issues, these lenses deprived the eye of oxygen and slipped out of the eye too easily. Over time, however, the diameter of the lenses reduced to improve wearability and with the arrival of soft contact lenses (using hydrophilic gel) their popularity grew. So what lenses will we be wearing in the future? The next milestone could be smart lenses, which have the ability to monitor a user’s health through a series of circuits, sensors and wireless technology. Meanwhile, the military is looking into telescopic lenses that will allow the human eye to zoom.

There are obvious advantages and disadvantages to both approaches – expenditure and downtime issues being two concerns. The investment cost for the all-in-one solution is higher because of the level of complexity involved. Also, if there is a problem anywhere in the machine, the entire production line stops and no lenses are produced at all. With a batch approach, there is more flexibility and operators have the ability to stop the injection moulding machine and compensate somewhere else in the system.

Automation equally plays a big role in maintaining cleanliness and efficiency levels, as well as reducing cycle times; each mould is typically produced in under three seconds. Tasks undertaken by these robots include unloading the mould tool and packing into sterile carriers.

In 2019, Gartner noted in its Hype Curve that regulatory constraints were likely to pose a challenge to the growth of 3D printing in the medical sector. Jacobson says 3D printing was able to fill the void at the beginning of the pandemic because regulators such as the US Food and Drug Administration relaxed their rules in order to meet demand.

If you buy something using links in our stories, we may earn a commission. This helps support our journalism. Learn more. Please also consider subscribing to WIRED

Covid-inspired 3D printing has not, however, revolutionised the medical device market in the way that seemed possible at the start of the pandemic. As coronavirus began sweeping the world 3D printing was able to meet a very specific need that arose because lockdowns in all corners of the globe meant supply chains instantaneously broke down. They were quick to recover, though, and while 3D printing filled a gap it has not, Gershenson says, stepped in to replace traditional manufacturing.

Large training hospitals were also making use of the technology, printing organs such as hearts so doctors could practice procedures over and over before moving into an actual surgical setting.

Assistance is also on hand for machine validation, including the Process Design, Process Qualification and Continued Process Verification stages. Although this can be a time consuming activity, the validation process is critical to ensuring moulders have a stable and dimensionally centred process that consistently produces high quality lens moulds.

“The FDA realised there was a need to become more relaxed and all regulatory bodies were putting out guidance saying ‘you need to be careful but we understand there’s a need for it’,” he says. “In the US they also limited liability, saying if you’re doing anything for Covid you can’t later be sued – pre-Covid, if traditional manufacturers didn’t realise there was something defective but there was a complication they could still be held liable. They can’t do that forever.”

Digital Society is a digital magazine exploring how technology is changing society. It’s produced as a publishing partnership with Vontobel, but all content is editorially independent. Visit Vontobel Impact for more stories on how technology is shaping the future of society.

“Before the pandemic hit, when we were trying to explain the model to people they would be like ‘what are you talking about?’,” he says. “The pandemic hit and people started printing PPE and now everyone and their grandmother is like ‘3D printing, local manufacturing, we totally understand it’.”

Direct drive machines offer major improvements in efficiency, including a reduction of up to 75% in energy usage during operation and improved repeatability and cycle times. However, manufacturers of hydraulic IM machines have recently made big strides to standardise the process to accommodate the variations in moulds and still meet the high quality requirements.

GETTING A QUOTE WITH LK-MOULD IS FREE AND SIMPLE.

FIND MORE OF OUR SERVICES:

Plastic Molding

Rapid Prototyping

Pressure Die Casting

Parts Assembly