More Sustainable Two-Component Overmolding - overmolding injection molding

Author:gly Date: 2024-09-30

During my time in the medical devices industry, I have seen several major changes. In 2010, when I started out, companies were still skeptical towards cavity pressure measurement. Those that went on to integrate the technology were mainly interested in using it for straightforward process monitoring, ignoring more sophisticated opportunities. When I joined Kistler, one major project was the creation of ComoNeo, a system which was a serious level-up to the previous solution ComoInjection. As a software designed specifically for injection moulders, ComoNeo provided a much better user experience and was quickly very successful on the market. It also attracted a lot of interest from the medical field. To meet the needs of medtech companies, we created a company-internal group to unite experts from the areas of plastics applications and advanced manufacturing. While the former bring a lot of material expertise, the latter have extensive knowledge in the monitoring of joining and assembly processes. Joining forces, the team saw the immense potential of gathering and analysing meaningful data in the medical field. This has lead to Kistler becoming the sole provider of the process navigator Stasa QC by Stasa, which enables the process monitoring system to provide efficient, automated documentation of the test plans and also to perform the corresponding process analyses. Most recently, we have also presented AkvisIO IME (Injection Moulding Edition), our inhouse process data solution to the broader public at Fakuma.

Industrial injection molding press machine for the manufacture of conditioner parts using polymers in the management of worker

One way to make use of AI certainly lies in the analysis of data and automated predictions based on them. The key here would be a data platform such as Kistler’s akvisIO. It integrates production and measurement equipment such as sensors or field devices and collects their raw data. It then processes it and overall makes data from different sources comparable to each other. Machine learning algorithms can then use the data to draw larger conclusions on the performance of the overall production set-up, to predict maintenance needs and even anomalies. Our vision is that eventually, the algorithm will be able to foresee events that have never occurred before. To make that vision a reality and to also get users on board with the new way of utilising data, our large team of data scientists focus on usability and user experience in our continuous development. AkvisIO processes and analyses process data to be directly used as a basis for decision making. This eliminates the additional step of interpretation and makes the data more accessible. Of course, the user can also add their own interpretation of the data to the results based on their own experience. As the need for AI continues to develop within the industry, we’ve set up akvisIO in a modular way. Working with customers and identifying their specific needs will allow us to add features, or specific modules tailored to a particular application or user group. One area of application could be advanced process control including trends and prediction, which could make processes even more efficient and robust, especially in terms of energy and raw material consumption.

Dairy Farmers replaced wooden crates with wire mesh crates to better work with those machines but the crates would bend and get stuck in the production line. "It became obvious to me that a better crate was essential," says Milton, and so Dairy Farmers reached out to plastics moulding company Nally. Together they designed a plastic crate for rounded "Perga" paper cartons.

Over the last ten years, measuring quality assurance throughout production has become industry standard because it provides reliable information about the quality of both process and product. Equally, digitalisation and automation of process monitoring have come a long way. Daniel Kormann, head of business development for plastics at Kistler, discusses the state of process monitoring and process control in the light of current developments such as AI and new regulations.

Quality management and quality assurance is essential in the medical industry as companies manufacture highly sensible products. Regulations such as Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) in the US and Medical Device Regulations (MDR) in Europe require companies to comply with strict and ever more extensive standards. They have to keep an impeccable paper trail throughout the entire production processes, just as the saying goes: “If it hasn’t been documented, it doesn't exist.” This need for full documentation puts a lot of pressure on companies. It increases the demand for integrated process solutions that both document and optimise all relevant process parameters. The ComoNeo process monitoring system by Kistler, for instance, accurately measures the pressure in all cavities and compares the resulting curve with the nominal curve. ComoNeoPREDICT uses artificial intelligence to predict product quality based on cavity pressure and temperature curves. All things considered, I believe that there is still a lot of untapped potential for digital solutions.

He says he has been "laughing his head off" at the furore over the City of Sydney's plans to build a 13.7-metre-high milk crate sculpture in Belmore Park. "I don't see the artistic merit even now," Milton says. "It was purely utilitarian."

While algorithm-based systems are already in use, there are two areas where we can improve and promote their reception. Firstly, when it comes to convincing companies of a solution they haven’t tried yet it is important to demonstrate that automated systems for the shopfloor are easy to set up and use. We will be working more closely with our customers to learn from their experiences, to improve our products as a whole and, as a result, to enhance their user experience.

As for Melbourne artist Jarrad Kennedy's claims that Hany Armanious' Pavilion sculpture is a copy of his own giant-crate-in-a-park work, Court, from 2005, Milton echoes what many commenters and social media snarks have pointed out since the story broke: if anyone should be suing, it's the guy who designed the original container.

Secondly, education is crucial. Educational opportunities are not only helping companies to see the benefits of a digital solution for their specific use case, but also to support employees on different levels in using them. That is why we have established the Kistler Plastics Academy. Here, we support our customers’ digital journey on three levels. On the basic level, we provide training for machine operators, application engineers and mould makers on how to install sensors, how to use the ComoNeo process monitoring system and the data base. On the advanced level, process engineers and production experts learn what is really happening inside the injection mould. On the expert level, data managers and quality engineers get insights into the potential of data management and data analysis.

And his memory is sharp. Over the phone, and in a follow-up 750-word essay entitled Short History of Milk Crates in NSW, Milton explained how he dreamed up the design of the milk crate.

Milton is not interested in money or even recognition – he says he doesn't want to "blow his own trumpet". But he has been tickled by the idea that something so utilitarian is being hailed as art.

Currently, there are software modules and algorithms that allow injection moulders to automatically adjust process parameters if the measurement curve deviates from a previously defined ideal curve. For instance, if the cavity pressure measured by direct, indirect or non-contact sensors is too high or too low, the system can adjust the switch-over point automatically. The Multiflow software module by Kistler balances filling multiple cavities very efficiently. It analyses fill-time differences between the cavities based on cavity pressure. It then adjusts the tip temperature of the hot runner automatically to achieve a more simultaneous filling. Using automation is becoming ever more relevant as we look at a growing shortage of skilled workers on the shop floor.

Plenty to laugh about: Geoff Milton, a former engineer with Dairy Farmers, was behind the milk crate design we know today.Credit: Steven Siewert

The inventor of the modern milk crate would like to thank Sydney's art world – you've given him a good laugh this past week.

Milton found further inspiration on a 1962 study tour of Europe and came back with an idea for a plastic crate for one-pint bottles; again he worked with Nally. The new crates maintained their shape, which was essential as the company moved into mechanical stacking and transport. "I like to think that all this must have saved hundreds of strained arms and backs," he says.

Milton, who lives in a Glenhaven retirement village with his wife Mary, is a spry 89 – when Fairfax Media called him late last week he had been digging in the garden and apologised for the delay getting to phone: "At my age it's a bit tough getting off your knees."

"I was just a young fellow who had bright ideas," says Geoff Milton, the 89-year-old Glenhaven man whose keen engineering skills gave us the milk crate we know, love and occasionally sit on today.

Within our focus industries, the circular economy and especially the use of recyclates are currently the most pressing topics. While we don’t see the latter reflected in the medical field yet due to regulations, this could change soon if we can provide a solution which reliably and automatically compensates process fluctuations. When companies start to use larger percentages of recyclates in their manufacturing processes, measuring technology becomes even more important, while it will not change as such. Melts containing recyclates have a fluctuating viscosity and as a result, parameters which indicate viscosity changes such as cavity pressure need to be constantly monitored to ensure a high product consistency. Again, AI could also come into play to detect and even predict anomalies.

It began with a perfect storm in the milk-delivery industry: the disappearance of the 1940s "Milko" who delivered milk into your billy can on a horse-drawn cart, a rise in consumer demand for sealed containers and the installation of new, fast-moving machinery at the factory end.

He is also tickled by the idea that one day his three great-grandchildren will walk through an oversized version of his humble creation in the centre of town. But he is not interested in seeing Armanous' creation when it opens. "Why should I see it?" he asks, chuckling. "I know it well enough."

The current crate we see came from public demand for milk in cartons in the late '60s; these cartons fitted neatly together in square boxes. "The first of these was a four-sided box with a few stiffening ribs," he says. But the crate – solid on the sides – proved too popular. "People were using them to store toys and potatoes, fair dinkum," Milton ays. "Our crate losses were not insignificant."

Milton was part of a team at Dairy Farmers Cooperative Milk Company, which, in the 1950s and '60s, worked on a series of crates for transporting cartons and bottles that would evolve into the now ubiquitous perforated plastic cube.

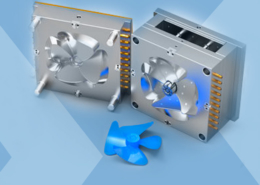

GETTING A QUOTE WITH LK-MOULD IS FREE AND SIMPLE.

FIND MORE OF OUR SERVICES:

Plastic Molding

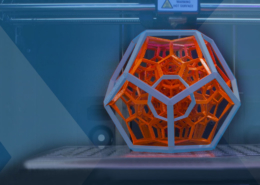

Rapid Prototyping

Pressure Die Casting

Parts Assembly